|

How

to Use A Compass

How to use a compass is a

question many walkers seem afraid of addressing. This section sets our the

basics in simple terms. Some think it is complicated. It isn't but like

many things in life, practice increases confidence.

The number of call outs to

Mountain Rescue Teams is increasing because too many people are relying too

heavily on mobile phones for navigation and heading to quite

difficult/dangerous terrain with no map or compass. Please spend a little

time working through the guidance below.

It is important

to be able to use a compass. It could save you from taking completely the

wrong route which in itself can be dangerous or the walk could end up being

considerably longer than anticipated, perhaps beyond the endurance of you or

some of your party. Most walkers start from a parked car and you need to be

able to get back to it.

Of course, on a

bright sunny day, with a clear path and good visibility with clear visual

reference points, you may not need to use a compass. But, what if you are on

a featureless hillside or moorland with an indistinct path and/or mist or

cloud suddenly descend.

Just as you are

right or left handed, you are also right or left legged, i.e. you have a

dominant leg. In thick mist with no visual reference points, you will walk a

circle - a bit like a rowing boat with one oar. You cannot consciously

change this. I have done it myself when I was too lazy to get out

the compass and over confident that I knew the way. These are the sorts of occasions when the compass comes into

its own.

It is not necessary to spend a

fortune on an effective compass. You can get one for under £20. The best

known range is probably Silva.

To be most effective

in its use, you need to know, at least approximately, where you are. Therefore, use it

sooner rather than later.

To state the obvious, the red

section of a compass needle points north. In relation to North, at 12

o'clock, East is at 3 o'clock, South at 6 o'clock and West at 7 o'clock. If

you never use a compass to any great extent than that, it provides a quick

reference at any point, as to whether you are going in roughly the direction

you should.

Navigation becomes more accurate

when you relate it's readings to an OS map, To make the excruciatingly

obvious point, the top of a map is north, bottom south, left west and right

east. No doubt you knew that (sorry) ........... but just in case.

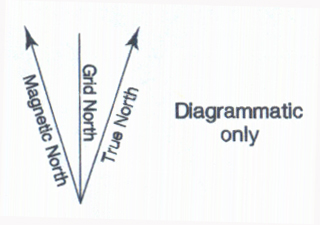

On OS maps, you

will see the diagram on the right.

Accompanying

it will be a statement such as:

"At the

centre of this sheet true north is 0º 59' east of grid north. Magnetic

north is is estimated at 2º 09' west of grid north for July 2007. Annual

change is approximately 09' east.

Magnetic data

supplied by the British Geographical Survey."

Already the

cries of "gadzooks" or worse no doubt! In

fact, we can instantly reduce the complexity by a third. True north is of no

use to us at all. We only care about the grid north (which not surprisingly

relates to the grid on the map) and magnetic north (where the compass

points). Forget

about true north. We will not mention it again. We

will look at the crucial parts of the rest of the statement shortly but first let's

look at a simple compass (simple but quite adequate)

We

have a clear plastic base. Along two sides are small rulers to help measuring

distances. The clear round "hole" is a magnifying glass (some map

print is quite small after all). The black arrow next to the magnifying

glass will indicate the direction of travel. In

this case, the

black ring (or bezel) is marked at 2º (i.e. 2 degree) intervals, 360º

being the complete circle. However, check the intervals on any compass you

buy. Note under the "N" is a small fixed white line,

difficult to see on the picture. Just bear this in mind for now. The

bezel is attached to the compass base, the part

with the red arrow and the 6 adjacent parallel lines. The bezel turns on the

baseplate. The red and white needle is the magnetic compass itself and the

red part always points north. Returning

to the statement, which we will examine in two parts. "Magnetic

north is is estimated at 2º 09' west of grid north for July 2007." Degrees

are divided into "minutes", 60 of them in each degree. In this

case magnetic north is 2 degrees 9 minutes west of grid north in July 2007.

You cannot meaningfully measure to minutes on a simple hand compass so

simply round anything under 30' down and over 30 up, to the next degree. "Annual

change is approximately 09' east." Although

a magnetic compass always points to magnetic north, unfortunately, magnetic north moves,

albeit only minutely. The OS note tells you by how much.

However, an annual change of this level is tiny and it will be a year or two

before we need to round up to 3º . Our adjustment is therefore 2º.

We will come back to this in a minute. Here

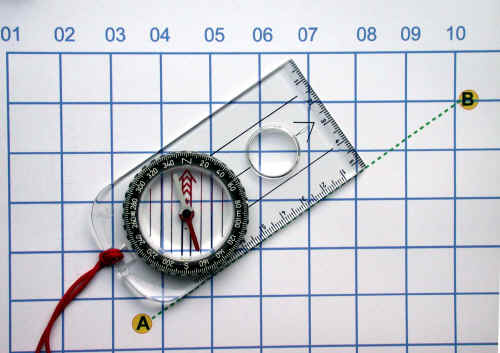

is a facsimile of a map which is kept rudimentary so that the grid lines

stand out. Assume

you want to get from point A to point B where perhaps there is a footpath but it is

indistinct and point B is somewhere in the mist.

Simply

lay the compass on the map with its edge along the route you wish to travel,

with the large black arrow in the direction you want to go.

Twist the bezel so that the lines within on

the base are aligned with the grid lines on the map with the "N"

of the bezel to the top of the map. As you can see, the needle itself is

pointing roughly to the bottom. Don't worry about that. At this stage, it

can be pointing anywhere. The

next step is to adjust for the extent to which magnetic north is not aligned

with grid north. If we take a close up view of the

bezel, you

can see that just to the left of the 60º mark a small but longer fixed

white line on the baseplate below the bezel we mentioned earlier.

The small white markings between the 60 and

40 each represent 2º. As magnetic north is 2º west of grid north, we

adjust by rotating the bezel one small mark anti-clockwise using the fixed

black line on the base as

a guide. Relative to grid north, the "N" mark on the bezel and the

red arrow (not the needle) are now

in the direction of magnetic north, relative to the map.

Now

remove the compass from the map, hold it horizontally and allow the needle to point itself to magnetic north and

slowly turn the compass until the red of the needle is inside the red arrow on the

base. Now

simply follow the direction arrow below, keeping the needle inside the guide

on the baseplate..

With

a very small deviation of magnetic north from grid north (i.e. only 2º) it

is arguable whether it is worth making the adjustment. E.g. just align with

the grid lines. Over short distances, this would no doubt be fine. It is

only over longer distances that the error would become significant. And,

it doesn't hurt to be accurate in any case! Remember

the dominant leg? Well in poor visibility, even following the arrow you

could still veer off. It is best to aim the arrow at something, even a

tussock of grass or a specific rock some distance away, walk to that, then

"take aim" at something else. In this way, your route should

remain straight. In the absence of any suitable objects, you could guide a

companion to a suitable position, walk to him then repeat. In

theory, if you are lost, you can determine your position by reversing the

above process namely, point the direction arrow at a known landmark, turn

the bezel until the red of the compass needle is within the red arrow then

put the compass on the map with the red arrow aligned north with the grid

lines and the side of the straight side of the base against the same

landmark on the map. If you do this with a second landmark, where the lines

cross will be your position. More accurate is to take three readings. You

should be in the centre of the triangle. Once again to be accurate, you could adjust for

the magnetic deviation. The

difficult part can be determining a landmark with certainty and it could be

impossible in reduced visibility. A mountain you

think you know can look different from a different direction. Is the church

spire in village A or village B? By far the best option is not to get so

lost in the first place, by regular reference to the map and of course by

not relying solely on a route from a book.

It

may help to orientate yourself if you “set the map”. This term refers to

positioning the compass on the map so that its north marking is aligned with

north on the map, as follows.

Turn

the bezel on the compass so zero degrees or ‘N’ is aligned with the

direction arrow on the base plate.

Holding

the map flat, align the edge of the rectangular compass plate with the

north/south grid lines so that the direction arrow points north.

Keeping

the compass in the same position on the map, turn them both so that the red

needle lines up with the north/south indicator on the compass. The map will

then be oriented with reality and you should be able to recognise the

features in front of you.

A

term you might come across relating to navigating with a compass is

"aiming off". Let's assume that point B on the map below is the

corner of two walls, indicated by a black line (as indeed it would be on a

1:25000 scale OS map) and that the corner is crucial to following your

route. If visibility was poor and you erred slightly following the compass,

you could end up too far north, miss the corner and finish up who knows

where. In this case, it would be better to aim further along the wall

indicated by the blue dotted line, to be certain of hitting it, then turn

left to follow it to the corner.

.jpg)

One

tip, it is worth working out compass bearings from strategic points on a

walk (e.g. from a trig. point) before a walk and writing them on a

piece of paper to slip into your map case. It is much easier and with less

chance of error to do this in

the comfort of your home/car than in a howling gale with the rain beating

down on a mountain top! Finally,

trust your compass. If it is not directing you in the direction you expect,

it is not likely to be the compass that is wrong! However, it needs to be

kept away from metal objects when you are using it and avoid putting it near

anything magnetic, which can (exceptionally) reverse the polarity. It this context, beware

any magnetic fastenings on clothing or bags. If there are two of you, it is

always worth checking your companions compass too. You have more chance of

winning the lottery than two compasses being wrong! If

you are flush with cash, a GPS receiver can not only tell you exactly where

you are but also do the entire navigation for you. Do bear in mind that they

need a clear view of the sky so can be ineffective under heavy tree cover.

Using

Map and Compass Reading List

Visit the Happy Hiker

Hiking

Store to buy compasses.

All information on this

site is given in good faith and no liability is accepted in respect of any

damage, loss or injury which might result from acting on it.

|